Short Vine’s first edition came out in the Spring of 2003 and is still published by undergraduates at UC today. To learn more about Short Vine’s history, I interviewed founder Katie Hartsock and previous faculty advisors Jay Twomey and Kristen Iversen to learn more about how the journal came to be and how it has evolved over the years.

Founding Team

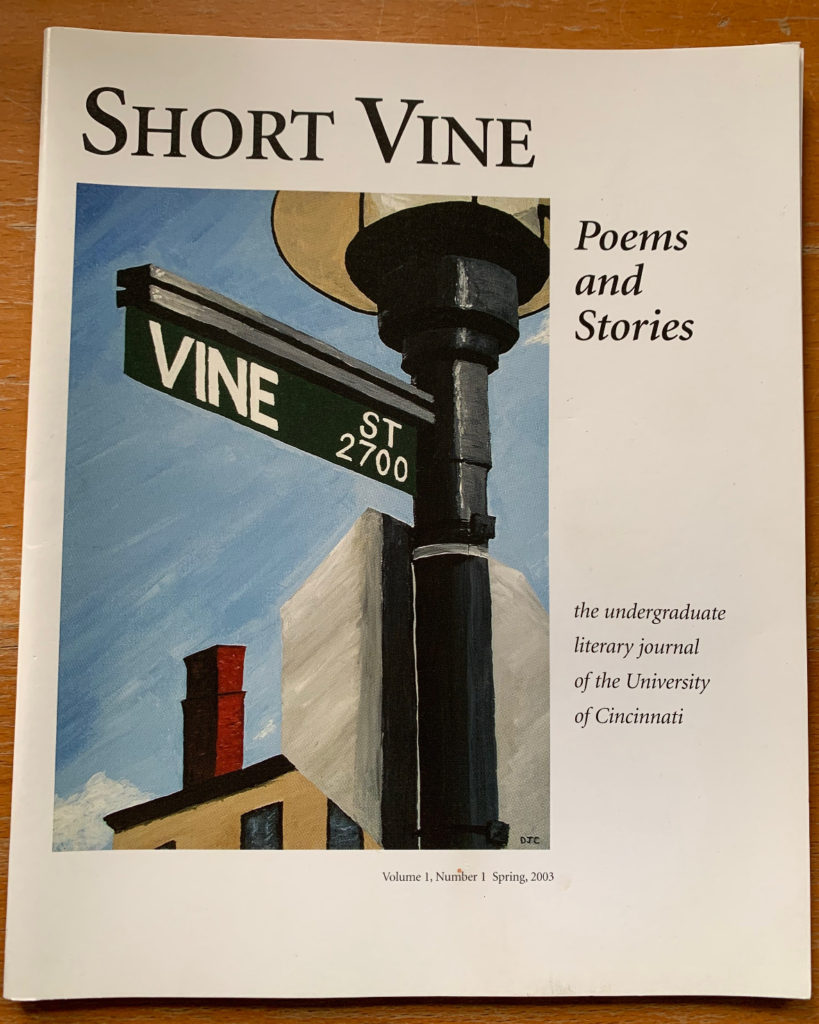

Katie Hartsock founded Short Vine in her junior year at UC, where she was double majoring in English Literature and Classics and pursuing a certificate in Creative Writing. I asked Hartsock about the members of the first editorial team, and she said it “was basically just a group of friends.”

Inspiration, Funding, and a Faculty Advisor

When I asked Hartsock what inspired her group of friends to create Short Vine, she talked about the tight-knit undergraduate writing community in the early 2000s and Cincinnati’s fantastic visiting readers. She said, “I was there at a time when the undergrads were really taking advantage of that.”

There used to be receptions in the faculty lounge after readings, where Hartsock had the opportunity to hang out with distinguished poets like Robert Hass and Linda Gregerson. She talked about how the literary community was “just so fun and fantastic.” She continued, saying that there was a real desire to create more opportunities for undergraduate writers to get involved in an environment that has a “learning curve [that] can be really steep for undergrads. It’s a whole new world.”

Jim Cummins, who oversaw the Elliston Poetry Room at the time, served as the faculty advisor; the Elliston Fund donated money for Short Vine to be printed, and so Short Vine was born.

Picking a Name

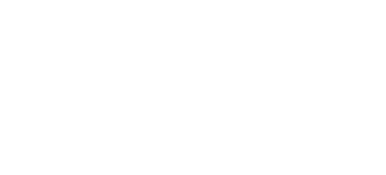

But how was it named? I asked Hartsock about the process of naming the journal, and she said, “We chose Short Vine for the name of it because the actual Vine Street goes all the way downtown, so it’s a link between campus and downtown… you could leave campus and go explore other neighborhoods in Cincinnati.” According to Cincinnati Refined, “Short Vine is Corryville’s five-block stretch of Vine Street that runs from Corry Street to Martin Luther King Drive.” Hartsock also said that “something about ‘vine’ always feels literary.”

Later, she asked me if Sudsy Malone’s Rock ‘n Roll Laundry & Bar, which was a bar and music club that once stood across from Bogarts, still existed. It doesn’t, but according to Cincinnati Magazine, “The dim bar ran the length of the front room in front of a mosaic of band photos. Washers and dryers were lined up in the back.” This seemed to be a central location for UC undergraduates at the time. Hartsock also talked about Daniel’s Pub and all the tattoo parlors on Vine Street.

She said that Short Vine became “a phrase to use [when someone] talked about that one street with the bars that played punk music.” It seems that to undergraduate students in the literary sphere, Short Vine felt like the epicenter— the heart of Cincinnati.

Submissions

One aspect that was particularly interesting to learn about was how the submission process worked in Short Vine’s early days. Undergraduate students from around the world can now submit to Short Vine, but it was initially just for UC students.

Hartsock described printing flyers and going to creative writing classes to encourage students to submit to the new journal. Submissions were all paper; students would have to print their writing out and drop it off in the cardboard box that served as a mailbox outside of the English Department mailroom.

Hartsock said, “It was a time where even though people used email to communicate, most assignments were still turned in hard copy.” However, the editorial team would let people know about acceptances or rejections through their emails.

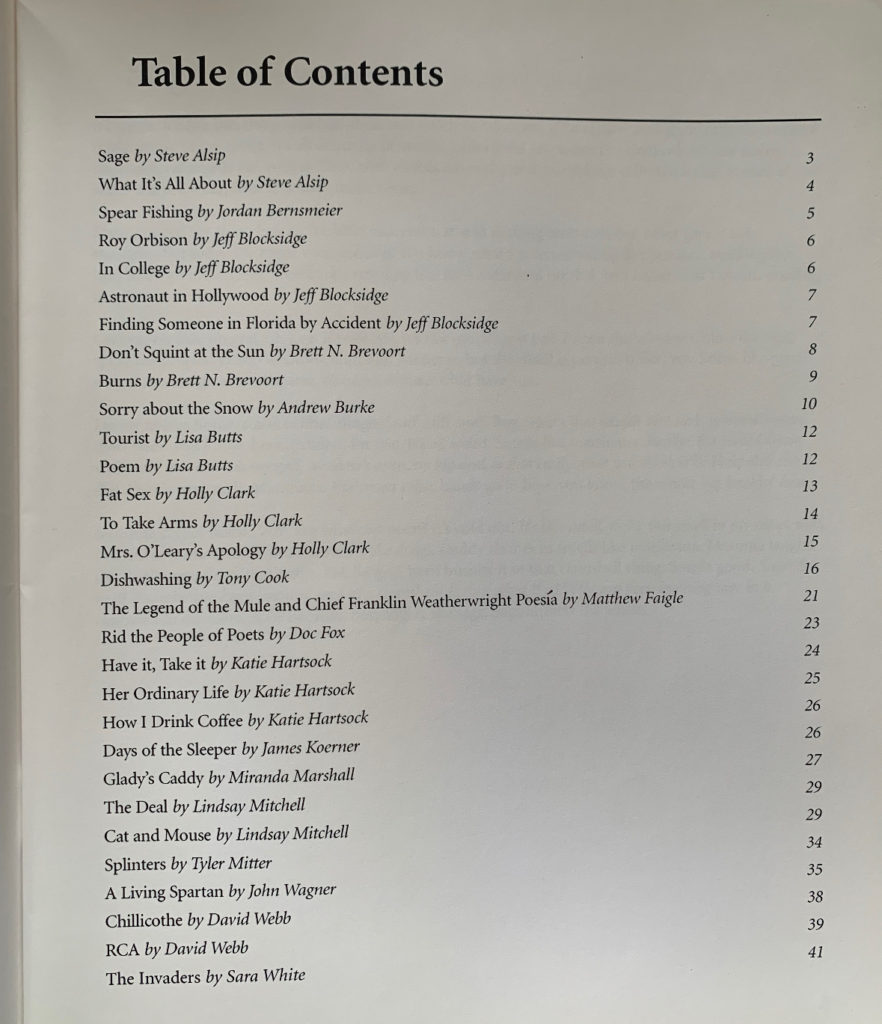

When I asked about the acceptance process, Hartsock said, “It was not an anonymous or impartial process. I remember there being a little bit of awkwardness with some people.” She added that “We probably published most of what we were given. It really felt like a way to bring all the undergraduate writers together and celebrate the really cool community we had. It was mostly a gesture of fun and community and appreciation of each other’s work.”

Creating the Journal

In essence, Short Vine was originally crafted with the spirit of zine culture in mind. Hartsock said, “We hung out at my apartment and read all the submissions and it was great. It was really fun. My roommate did the cover.” Hartsock and her college roommate Darci Cooper still remain best friends; they were both bridesmaids at each other’s weddings.

At the time, there was no art and photography genre— this was part of the low-budget nature. The final journal ended up being only 46 pages. When I asked about Cooper’s cover art, which is a painting of the Vine Street sign, Hartsock said, “Maybe there were funds to pay her 50 dollars or something for doing it, which to her in 2003 felt like a big deal.”

She talked about maybe having a reading at one point after the journal came out, saying that it must have been at Cody’s Cafe, a restaurant on Calhoun Street.

Short Vine’s Impact on Hartsock

After her undergraduate career, Hartsock went on to obtain her MFA and Ph.D. and is now a professor at Oakland University. Her new collection of poems, Wolf Trees, is currently available to buy on prerelease from Able Muse Press and will be officially out on September 15, 2023.

I asked Hartsock about how her experience working on an undergraduate journal has shaped her career, and she said, “Looking back, founding Short Vine, being with friends who were writers and excited about writing and publishing, taking risks— that was completely foundational to my whole career. Being part of the group gave me the encouragement to apply to MFA programs… It made me really love the world of writers and want to be a part of those conversations.”

Jay Twomey’s Time as a Faculty Advisor

Short Vine continued after Hartsock graduated. Jay Twomey became an advisor of Short Vine sometime around 2010 for a year or two. At the time, he was the Undergraduate Director for English, and he worked to reinvigorate an undergraduate student organization in English that had lapsed. Part of rebuilding the English community was reinvigorating Short Vine.

As an advisor, he helped promote the journal and encouraged students to submit. He remembers that it was a volunteer-based organization and that some of the same students involved in the undergraduate student organization were also working on Short Vine.

I asked Twomey about his role as an advisor, and he referenced being an editor of Soundings East at Salem State University. He said, “I remember it being totally student-driven, so when I became the faculty advisor [of Short Vine], I was totally hands-off. It depended on the taste of the students involved.” I asked him about his experience working on the Soundings East, and he said, “It was helpful probably in some way to have that organizational training and to actually communicate with vendors about the printing, paying, and selecting. I felt like I was totally in over my head.” The culture of allowing students to make decisions around the selection of pieces and creation of the journal has remained throughout the years.

Twomey later recalled that Michael Hennessey took over for a couple of years, helping to establish Short Vine’s digital presence. While the journal was originally only in print, it evolved to be both print and digital; now, Short Vine is only published digitally.

Kristen Iversen’s Time as a Faculty Advisor

After Hennessey, Iversen took over as the faculty advisor. While Short Vine had always functioned as a student-led organization, she wanted to create a class that taught students about the publication and editing process. She had success creating class-run undergraduate literary journals in the past for other universities, so she introduced the idea of making Short Vine a class experience to the English Department around 2018. Her idea was met with support and encouragement.

Iversen’s goal was to “enhance and develop a really dynamic undergraduate journal” and for the students to gain practical job skills. Short Vine students learn to solicit manuscripts, work with authors and artists, edit submissions, develop a website, and market the journal.

I asked Iversen about the decision to transition the journal into a course, and she talked about how having Short Vine run through a class creates a sense of accountability and responsibility— something that isn’t always easy to cultivate in a volunteer-based organization. She went on to say, “It’s more than just getting a grade. It’s a product. It’s a really exciting, creative entity, and it’s something that you can put on your resume. It’s something that exists in perpetuity.”

I also asked about some of the most important elements that students learn in the class. She talked about the importance of discussing and developing aesthetic criteria for each genre and the class as a whole. While the four genre groups (poetry, fiction, literary nonfiction, and art and photography) change every semester, Iversen said that “the journal has developed a very distinct identity and a sense of voice.” Students are encouraged to think about everything they learn in regard to their own work.

Iversen still has copies of the undergraduate journal she worked on at the University of Colorado, Boulder. She said, “[This experience] made me decide to go on and get a Ph.D. and publish books and be a writer. For me, it was very fundamental. It was a really fundamental experience.”

The Importance of Undergraduate Literary Journals

Undergraduate literary journals can be fundamental to a writer and artist’s development. Short Vine’s editors have been (and will continue to be) shaped by their experience working on the journal.